Yesterday I posted a VERY long post that, in hindsight, I think was too long, put two different topics side-by-side in one post, and also buried at the end some material that I think ought to be put out there on its own, just for the record if nothing else. So I chopped yesterday’s post in half, and am posting the second half (my thoughts on the 1987 Moot Court Trial in Washington DC, then and now) separately in this post. It also affords me the opportunity to add some further thoughts based on one of the presentations given at the just-concluded Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference at Concordia University in Portland (OR).

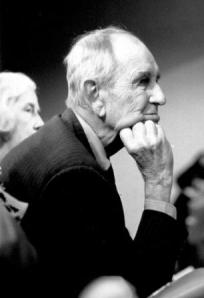

Charlton Ogburn listens intently during the Moot Court Trial. (Photo credit Bill Boyle, all rights reserved)

In 1997 I was the editor of the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, and wrote our lead story for the summer 1997 issue, which was a 10th anniversary appraisal of the impact of the Moot Court. Given the historic events at the Folger last week (i.e., the “Shakespeare and the Problem of Biography” conference), I thought I’d reprint the bulk of that article here to provide some history and context on where we’ve been, and where we are undoubtedly headed, which is, simply (as we all hope) to the truth about who Shakespeare was (i.e., Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford), and how and why he became “Shake-speare.”

There were two things on my mind in re-visting the Moot Court Trial through the 1997 article:

1) First, it makes the point that Ogburn’s The Mysterious William Shakespeare (published in 1984) precipitated the event, along with several other major events in the 1980s, all of which set the stage for the next 25 years. And along the way the events surrounding the trial show how fast and loose opponents of the debate can be (and have been, and still are) in obstructing progress (what a surprise). In my own humble opinion, it was Ogburn’s book that lead — inevitably — to the Folger’s “Problem of Biography” conference last week. True, much has happened since TMWS was published, but it clearly set in motion the great advances that have taken place in the authorship debate over the past decades, and that should not be forgotten. Thirty years ago the idea of the academy dealing with the biography of the Stratford man was a non-issue, and text was king. Today the bunker-like Folger is under siege on the issue, and has no good answers. This year is the 30th anniversary of the publication of TMWS, and some recognition should be made of how important it was in getting us to where we are.

2) Second, the Trial itself gets right to the question of “What happened and Why?” I discuss in the article this problem of how to characterize just what took place 400 years ago that resulted in the author of the greatest works in Western Literature being deprived of his due credit, and even, in fact, being erased from history altogether. In 1987 the exchanges that took place over the word “conspiracy” were quite revealing, as were Ogburn’s own thoughts on the matter. The word itself has become so demonized in our present culture that using it almost automatically leads to ridicule. Yet we are then left with the question, “Well, what did happen, and how do we describe it?” And if what did happen was that a handful of individuals “conspired” to misrepresent the truth and hand down to posterity a false history, what word can we use? Readers should note what Justice Stevens said in his closing remarks about conspiracy.

This debate over conspiracy (both the word and the concept) has raged on for the past thirty years. Just what do we mean by “conspiracy?” At the Folger conference last weekend I had some interesting conversations with several colleagues about this very question. And then, just this past weekend, one of the presentations given at the authorship conference in Portland (“The Use of State Power in the Effort to Hide Edward de Vere’s Authorship of the Works of William Shakesepeare,” by James Warren) laid out a well-reasoned argument for just what may have happened (and why), all without using the dreaded “C” word. What Warren discusses in his presentation dovetails nicely with some of what was said in 1987 about these questions of “What happened?” and “Why?” They are important questions that must be dealt with, sooner or later.

I’ll be posting more on this in the coming weeks, but I did want to get my reprint of the Moot Court article out there in a way that wouldn’t get overlooked, and that emphasizes this important issue. As we all love to say, “Stay tuned.”

Following is an edited version of my article. A PDF of the complete article is available here (SON33.3 (Summer 1997)_Boyle_1987 Moot Court Trial), and includes some more pix and a one-page sidebar article on the Shakespeare Oxford Society’s 11th annual conference, held the day after the debate.

The 1987 Moot Court Trial – “Ten years later the verdict is in: Edward de Vere and the Oxfordians won”

The events of September 25th-26th,1987, in Washington DC should eventually be known as one of the true watershed moments in the history of the Shakespeare authorship debate.

Justices Blackmun, Brennan and Stevens listen to arguments during the 1987 Moot Court Trial on the Shakespeare authorship question. The event was covered on C-SPAN and made the front pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post the next day. (UPI photo)

First, there was the Moot Court Trial, held on Friday, September 25th, at American University, with three Justices of the United States Supreme Court presiding. This event attracted mainstream media coverage of the authorship debate such as had never been seen before in this century. And while the official result was a seemingly decisive 3-0 verdict for the Stratford actor, the true story from that day is that two of the three Justices presiding actually began a journey which eventually brought them to Oxford’s doorstep in the 1990s (along with many hundreds of other former Stratfordians).

Meanwhile, at the 11th Annual Conference of the Shakespeare Oxford Society (held in conjunction with the Moot Court event), history was also being made. The turnout of new Society members from around the country, all gathered together for the Moot Court, resulted in well-attended morning and afternoon meetings on Saturday, September 26th, which in turn resulted in the near tripling of the size of the existing Board of Trustees (from 5 to 14 members), and the beginning of 10 tumultuous years of growth and change. (See page 9 for a separate story on the 11th Annual Conference.)

There are undoubtedly a number of our current members who first became aware of the authorship issue through publicity immediately surrounding the Moot Court, or six months later through the James Lardner article on the event in The New Yorker (April 11,1988). […]

Looking back on all this 10 years later it is clear how far the Oxfordian cause has come in so little time. What has also become clear over these same 10 years is that some key questions are still with us today, questions about how to debate the authorship issue, how to publicize it, how to deal with the inevitable controversies that come along with it (controversies both with our adversaries and among ourselves) — in short, questions over how, ultimately, to prevail.

Charlton Ogburn has said, in 1987 and still today, that he was against this idea all along, believing that a narrowly focused legal proceeding could never do justice to the debate. However, as Oxfordian David Lloyd Kreeger pressed ahead with his plans for the Trial, there was an understanding that the actual trial would be not so much a trial as a head to head comparison of the case for Oxford as presented in The Mysterious William Shakespeare, verses the case for the Stratford man as presented by his best advocate using the standard biographies and evidence.

Controversy first arose in the days before the Trial, when Ogburn got hold of James Boyle’s brief on the case (Boyle was defending the Stratford man), and much to his horror found it to be page after page of what he considered to be boiler-plate Stratfordian arguments, combining the worst of such chestnuts as “All his contemporaries knew Shakespeare wrote the works” to what Ogburn considered some egregious misrepresentations of what he had written in The Mysterious William Shakespeare.

In preparing this article, Ogburn shared with us some of the letters he wrote in the months after the Trial. His chief concern was that attorney James Boyle’s entire brief felt to him as if it had been taken wholesale from some doctrinaire Stratfordian source, and Charlton more than once suggested to Boyle that he disassociate himself from such “slander.” Boyle never responded to Ogburn’s letters, but eventually, through a third party, Ogburn was assured that Boyle had indeed written the brief, and that he stood behind it.

A year later, however, Boyle did talk in print about the Trial, the authorship question, Oxfordians and Stratfordians in his article “The Search for an Author: Shakespeare and the Framers” American University Law Review 37:625(1988).

In the article’s first endnote Boyle dedicates the entire article to Samuel Schoenbaum, who, he says, allowed works to be part of the record for the case [i.e. the Moot Court], and further, who had recommended to Boyle “certain works on the subject.” Boyle goes on to state “I commend Mr. Schoenbaum’s beautifully written and charmingly humorous Shakespeare’s Lives to the reader as an example of what Shakespearean scholarship should be like.” Score one for the instincts of Charlton Ogburn.

There was more controversy on the day of the Trial. Justice William Brennan announced, in his opening comments, that the three-man Moot Court would follow more traditional legal proceedings, and that in the absence of a lower court ruling on this case (Shaksper vs. Oxford), Brennan ruled that the burden of proof was on the Oxfordians both to dismiss the Stratford man, and to establish Oxford — all in 1 hour! No similar burden was placed on the Stratford side.

Brennan’s surprising decision to place the entire burden on the Oxfordian side immediately illustrated what is probably the key issue in the authorship debate: to dispose or not to dispose of the Stratford man. Brennan stated that since his [Shaksper’s] claim went unchallenged for two centuries, it carried with it the presumptive weight of the law and it would take a “preponderance” of the evidence to take the works away from him (not just “reasonable doubts”). Justice Blackmun remarked to Brennan that “he hadn’t checked that with us [i.e. Blackmun and Stevens].” The exchange led to some laughter, but Charlton Ogburn was not one of those laughing.

With the burden of proof now totally on the Oxfordian side, the outcome of the Trial was a foregone conclusion. It also reinforced the importance of “disposing of the Stratford man” as a key issue whenever debating the authorship. Charlton Ogburn is quoted in the New Yorker article as saying, “You can’t get anywhere with Oxford unless you dispose of the Stratford man.” He repeated this point almost verbatim it us in our recent talk with him. And it’s easy to see why he feels this way. He cited in 1987 the experience of his parents with This Star of England, noting that “they made one terrible miscalculation. Until they got to the very last chapter, they didn’t even mention the Stratford man.”

The other key authorship issue that emerged during the proceedings can be summed up in one word: conspiracy. It is a word that neither Ogburn nor Society Vice-President Gordon Cyr is quoted as using in 1987, and in fact this word is completely absent from Lardner’s New Yorker report, although in the course of the Trial it made several prominent appearances.

Indeed, one senses that this was both Ogburn’s and Cyr’s chief concern in the days before the Trial. As reported by Lardner, Cyr worried about such matters as how many Oxfordians would show up, whether “fringe elements” would be among them, and generally how to cope with all the publicity. “Cyr was expecting…more Oxfordians, perhaps, than have ever been assembled in one place,” Lardner writes.

And in discussing what these “fringe elements” might bring up, Cyr stated that he had in mind such matters as the Ashbourne Portrait and the theory about Southampton’s parentage. A strange pairing of concerns, it seems to some of us today.

For while the Southampton issue rages on even today as a central and important piece of the whole story (and one which can open up the Pandora’s box of political conspiracy as part of the true story, Sobran’s Alias Shakespeare notwithstanding), the Ashbourne Portrait story now seems more like an interesting sideshow. The story in 1987 that concerned Cyr was the Folger’s rejection of the underpainting of the portrait as being the lost Ketel portrait of Oxford. But today that seems about as insightful as their recent attempts to deflect interest in de Vere’s Geneva Bible by claiming that Oxford didn’t make the annotations.

Meanwhile, early on in the Moot Court proceedings, Justice Brennan brought home this second key issue when he told Jaszi that the entire authorship debate sounded to him like a “conspiracy theory,” to which Jaszi immediately responded that a conspiracy was not necessary in a totalitarian society. This response sounds very much like what Charlton Ogburn has said for years, and which he repeated to us this year. “In a totalitarian society, it’s not conspiracy,” he stated. “Elizabeth’s word was final.” For some Oxfordians in 1987 this tactic (i.e., not even using the word “conspiracy”) seemed like a mistake, a matter of bobbing and weaving with our opponents rather than diving headlong into the seemingly unavoidable center of the issue. Somewhat later in our talk with Ogburn we returned to the subject of … “conspiracy,” and he remarked that, “[for anyone] to say no to ‘conspiracy’ is naive; it’s how the world works.”

At the end of the day, Justice Stevens had the last word, and he did not pull back from using the dreaded “C” word. He first brought a smile to Ogburn’s face when he remarked, “…I am persuaded that if the author is not the man from Stratford, then there is a high probability that it is Edward de Vere. I think his claim is by far the strongest of those that have been put forward.”

Justice John Paul Stevens was clearly sympathetic to the Oxfordian case during the 1987 trial, and just a few years later he came out publicly in support of Oxford. (NPR photo)

A few moments later, however, he cut straight to the heart of the debate and to this primary tactical dilemma that comes with it. “I would submit,” he stated, “that, if their [Oxfordians’] thesis is sound, that one has to assume that the conspiracy — I would not hesitate to call it a ‘conspiracy,’ because there is nothing necessarily invidious about the desire to keep the true authorship secret — it would have to have been participated in by [Heminge and Condell and Digges and Jonson] …in my opinion the strongest theory of the case requires an assumption, for some reason we don’t understand, that the Queen and her Prime Minister decided, ‘We want this man to be writing plays under a pseudonym.’”

“Of course,” he continued, “this thesis may be so improbable that it is not worth even thinking about; but I would think that the Oxfordians really have not yet put together a concise, coherent theory that they are prepared to defend, in all respects.”

Stevens’ words were a fitting conclusion to the Trial, and they ring as true today as they did ten years ago. He has since written on the subject of the authorship (“The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction” [published in the April 1992 University of Pennsylvania Law Review], clearly indicating his continuing interest and sympathies in the debate, while Blackmun has stated flatly (in the second edition of Ogburn’s The Mysterious William Shakespeare) that he would “now [1992] vote for the Oxfordians.”

In the ten years since much has happened, and at the Society’s Annual Conferences in the late 1990’s there are regularly four to five times as many Oxfordians gathered together each year as the 1987 turnout that so concerned Gordon Cyr.

[…]

… And last, but certainly not least, mention must be made of the importance of publicizing the authorship debate, something which the Moot Court Trial contributed to greatly, and which was followed by the Frontline documentary, The Shakespeare Mystery (1989), the Atlantic Monthly cover story (“Looking for Shakespeare,” October 1991), and such books as Richard Whalen’s Shakespeare: Who Was He? (1994). Now such efforts have taken on a whole new dimension with the phenomenon of the Internet. For here exists a venue where the debate can be experienced by thousands, and where there are no space or time limits for either presenting material or reaching a verdict.

… So it may be that Stratford’s Shaksper and his supporters will never be “officially” dislodged, neither by a smoking gun nor by a legal ruling. Instead, one by one future generations may simply—like Supreme Court Justices—leave Stratford, and soon all that will be left is a ghost town full of bewildered scholars, their legal claim to Stratford still firmly in hand, wondering what happened.